Oliver Stone is a fascinating figure in the film world. He began as a screenwriter in the 70s and 80s and wrote successful scripts for Midnight Express, Scarface, Conan the Barbarian, and The Year of the Dragon. In the mid-eighties, he got his first directing gig with Salvador and then hit a hot streak with Platoon, Wall Street, Talk Radio, and Born on the Fourth of July. In many ways, his films are pure representations of 1980s culture. His preoccupation with the conflicts, music, and intrigue of the 1960s along with his sharp critiques of contemporary 1980s excess and consumerism made his films potent and memorable documents of the decade.

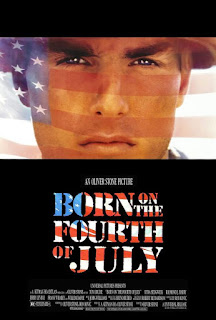

One film of his I hadn’t seen was 1989s Born on the Fourth

of July starring Tom Cruise. It’s based on the autobiography of the same name

by former Marine and disabled Viet Nam vet, Ron Kovic. Kovic is a gung-ho,

America-love-it-or-leave-it patriot who grows up in working class Long Island.

Relentlessly competitive, he volunteers for the Marines as soon as he’s

eligible and is sent overseas to fight. During his second tour in Viet Nam,

Kovic has a catastrophically bad day. All in one maneuver, he’s party to accidentally

killing a small village of old women, children, and babies; killing one of his

own men with friendly fire; and getting shot himself and having his spinal cord

severed with the bullet, permanently paralyzing him from the chest down.

The second two thirds of the movie revolve around Kovic

first fighting his disability, then succumbing to depression and bitterness and

alcoholism, and then finding new purpose as an anti-war activist, culminating

with the moment when Kovic addresses the 1976 Democratic National Convention

following the publication of his book.

Oliver Stone is not a restrained filmmaker. In fact, the

first movie review I read that ever really stuck with me as a kid was of Platoon and the reviewer wrote that

Stone “directs with all the subtlety of an earthquake.” And it’s true. He’s a

maximalist who layers on thick helpings of period music, extreme hair and

make-up, and sometimes far too close for comfort camera work. In the case of Born on the Fourth of July, his version

of late 1950s Long Island is as ideal and red, white, and blue as you can

imagine. His Viet Nam is saturated with sunlight and blood. The underfunded,

understaffed VA hospital where Kovic finds himself after his injury is

practically a Dantean circle of hell. I’m not saying these aren’t accurate

representations of Kovic’s real life experiences. It’s just that Stone’s middle

name might as well be “In Your Face.” Sometimes that intensity serves the story

and other times, it just makes you a little nauseated.

Born on the Fourth of

July was one of Tom Cruise’s first bids to be taken seriously as a “real”

actor instead of just a good looking kid with a megawatt smile. He hadn’t yet

developed the now tired Cruise-isms that have made so many of his recent

performances basically interchangeable, and he gives Kovic a real visceral

punch and vulnerability. With the exception of some pretty bad wigs, Cruise’s

transformation from 18 year old super jock to a middle aged man in a wheelchair

is convincing and his physical commitment to the role is apparent throughout.

The commitment paid off as Cruise was nominated for an Oscar and won the Golden

Globe that year for Best Actor. The film was nominated for a total of eight

Oscars and won two, including Best Director. Stone has produced a lot of

provocative, in-your-face films like Natural

Born Killers, JFK, and Nixon.

He’s still working today, and his most recent film was 2016’s Snowden. However effective his newer

films may be, it’s unlikely that Oliver Stone will ever hit another high point

like he did with his 80s hot streak that culminated with Born on the Fourth of July.